- My Forums

- Tiger Rant

- LSU Recruiting

- SEC Rant

- Saints Talk

- Pelicans Talk

- More Sports Board

- Coaching Changes

- Fantasy Sports

- Golf Board

- Soccer Board

- O-T Lounge

- Tech Board

- Home/Garden Board

- Outdoor Board

- Health/Fitness Board

- Movie/TV Board

- Book Board

- Music Board

- Political Talk

- Money Talk

- Fark Board

- Gaming Board

- Travel Board

- Food/Drink Board

- Ticket Exchange

- TD Help Board

Customize My Forums- View All Forums

- Show Left Links

- Topic Sort Options

- Trending Topics

- Recent Topics

- Active Topics

Started By

Message

re: Interesting Business, Econ and Finance Links

Posted on 12/14/20 at 12:25 pm to CorkRockingham

Posted on 12/14/20 at 12:25 pm to CorkRockingham

quote:

Yes, but I’m highly inclined to think that the commercial banks in the US are able to operate in the same manner. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be able to stay Liquid as discussed in John Adam’s article.

I haven’t been able to find a “smoking gun” in terms of whether or not US banks are able to “spend” those reserves, but I have to believe Lacy Hunt knows what he’s talking about. I trust his opinion perhaps more than anyone discussing this issue.

Posted on 12/14/20 at 12:28 pm to wutangfinancial

quote:

I'm in cash, miners and I trade tech options. That's good enough for me right now. I'll probably take a stake in EM after New Years. Not rushing before they have to add Tesla to the S&P and all of the rotation I expect the next two weeks. Who knows everybody's hedged though.

That sounds reasonable to me. Sounds like we’ve both taken a page out of Chris Cole’s left tail / right tail approach, although I’m sure he has a much more sophisticated approach to capturing long vol

Posted on 12/14/20 at 12:29 pm to RedStickBR

I think Lacey said that the banks have to in turn then lend out those reserves for it not to be deflationary.

Which they aren’t. That I understand when you look at the velocity of money.

Which they aren’t. That I understand when you look at the velocity of money.

Posted on 12/14/20 at 12:44 pm to CorkRockingham

quote:

I think Lacey said that the banks have to in turn then lend out those reserves for it not to be deflationary.

Which they aren’t. That I understand when you look at the velocity of money.

Right, that’s the same thing SVM says, and that’s because he’s probably been influenced by Hunt. QE can be massively inflationary, but it can also be deflationary. Depends on, as you said, whether banks sit on the reserves or lend against them.

Posted on 12/15/20 at 7:29 pm to RedStickBR

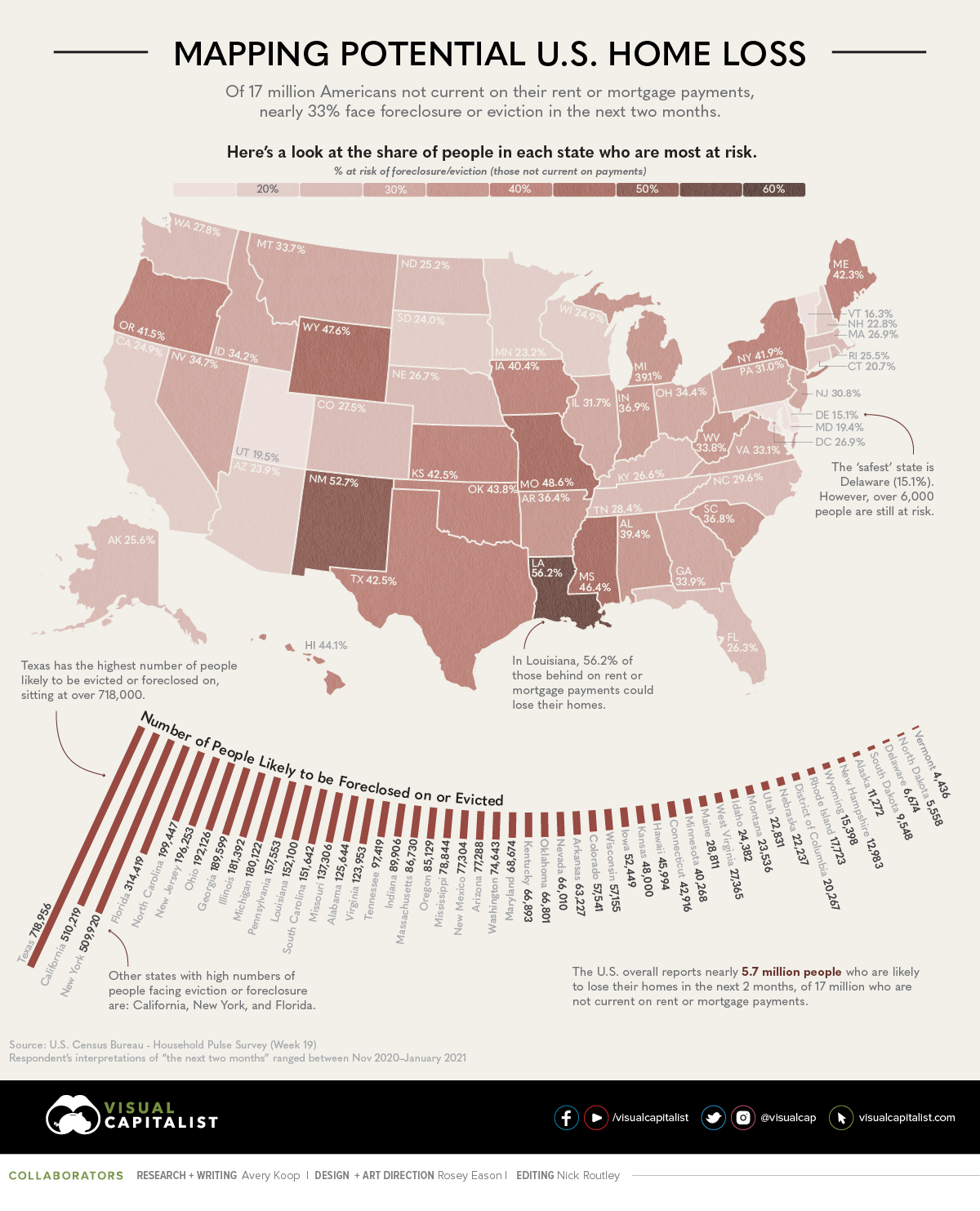

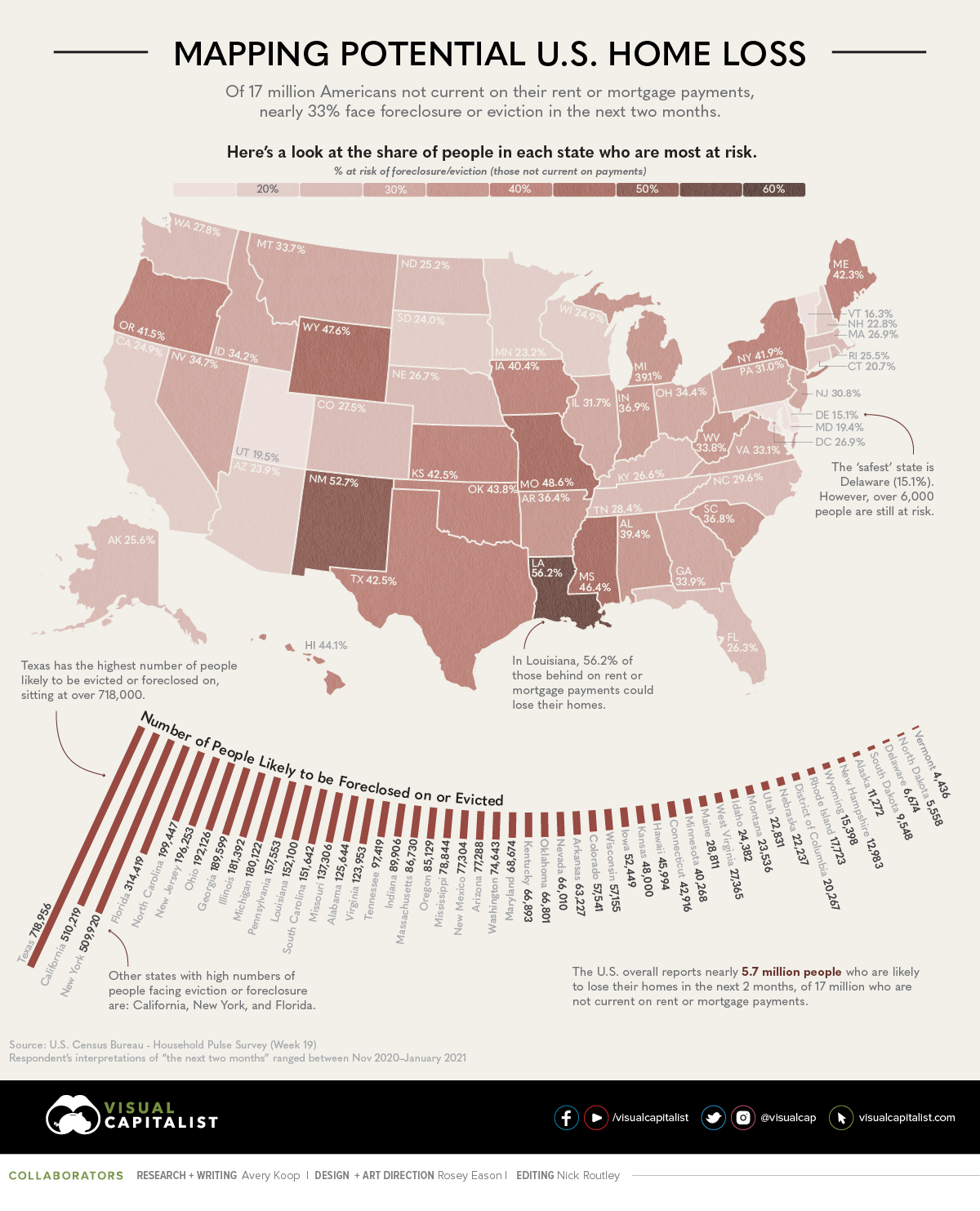

Louisiana projected to be worse than any other state in potential home evictions as a percent of those currently behind on rent or mortgage payments:

LINK

LINK

Posted on 1/11/21 at 9:15 am to RedStickBR

Thought of the day:

There's been much justification in financial circles recently for historically high P/Es on account of the fact bonds yields are historically low. In other words, the inverse of P/E (earnings yield) should be low to maintain a constant spread against historically low bond yields. Certainly, that argument makes sense on its face. But, a few things from Cliff Asness:

1. In his paper which he released just a few months before the dot.com bust, he argued against a similar line of reasoning that was prevalent then. The argument then, in his own words, was "low inflation and interest rates makes the earnings yield (the inverse of P/E) of equities more attractive vis a vis bonds."

2. However, he points out that high P/Es are justified by high growth, but that high growth tends not to coincide with periods of low inflation and interest rates.

3. He cites Modigliani and Cohn (Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 1979), who argued then that investors are mistaken to "make this comparison of equity yields to nominal bond yields." Asness notes that their view proved prescient in part by the fact the inverse of this argument, namely that high inflation and rates should result in high earnings yields and thus low P/Es, turned out to be horribly wrong over the ensuing decade (the 1980s).

4. His conclusion from Modigliani and Cohn just a couple months before the dot.com bust was that "their logic now obviously leads to the possibility of investors overvaluing equities today in our low interest rate, low inflation environment." I need not remind you what happened next.

5. Finally, Asness' own work from earlier that year (Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 2000), found that low interest rates do support a higher than normal P/E on stocks, but only for the short term. "In other words, Asness [found] that in the short-term investors mistakenly act like stock yields should move with nominal interest rates, but in the long-term discover that they should not."

With that in mind, and given a major contributor to today's richly valued stock market is this notion that valuations should be high because rates are low, where do you stand on this debate?

Related question: what, if you happen to be of this view, justifies today's sky high P/Es? Why are things "different this time" when compared to periods like 1929 and 1999?

There's been much justification in financial circles recently for historically high P/Es on account of the fact bonds yields are historically low. In other words, the inverse of P/E (earnings yield) should be low to maintain a constant spread against historically low bond yields. Certainly, that argument makes sense on its face. But, a few things from Cliff Asness:

1. In his paper which he released just a few months before the dot.com bust, he argued against a similar line of reasoning that was prevalent then. The argument then, in his own words, was "low inflation and interest rates makes the earnings yield (the inverse of P/E) of equities more attractive vis a vis bonds."

2. However, he points out that high P/Es are justified by high growth, but that high growth tends not to coincide with periods of low inflation and interest rates.

3. He cites Modigliani and Cohn (Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 1979), who argued then that investors are mistaken to "make this comparison of equity yields to nominal bond yields." Asness notes that their view proved prescient in part by the fact the inverse of this argument, namely that high inflation and rates should result in high earnings yields and thus low P/Es, turned out to be horribly wrong over the ensuing decade (the 1980s).

4. His conclusion from Modigliani and Cohn just a couple months before the dot.com bust was that "their logic now obviously leads to the possibility of investors overvaluing equities today in our low interest rate, low inflation environment." I need not remind you what happened next.

5. Finally, Asness' own work from earlier that year (Financial Analysts Journal, March/April 2000), found that low interest rates do support a higher than normal P/E on stocks, but only for the short term. "In other words, Asness [found] that in the short-term investors mistakenly act like stock yields should move with nominal interest rates, but in the long-term discover that they should not."

With that in mind, and given a major contributor to today's richly valued stock market is this notion that valuations should be high because rates are low, where do you stand on this debate?

Related question: what, if you happen to be of this view, justifies today's sky high P/Es? Why are things "different this time" when compared to periods like 1929 and 1999?

This post was edited on 1/11/21 at 9:20 am

Posted on 1/15/21 at 2:27 pm to RedStickBR

What do you think about the new admin's "relief" proposal?

Posted on 1/15/21 at 6:16 pm to wutangfinancial

I think we are seeing less and less effectiveness with each additional round of stimulus, just as Dr. Hunt said would happen. I also think this iteration is potentially disastrous if they succeed in hiking the minimum wage to $15, which would result in a net reduction in productivity and hence put even more pressure on Debt to GDP. Again, Dr. Hunt has warned against excessive debt, but especially when said debt is unproductive. A debt package, combined with a job-killing minimum wage hike, appears to me like a toxic combination in a 400% Debt-to-GDP world. Lastly, as others have said, this isn’t “stimulus,” it’s “sustenance,” even moreso in light of the news drip coming out that the job market has rolled over and the vaccine rollout will be slower than anticipated.

Posted on 1/25/21 at 1:50 pm to RedStickBR

Posted on 1/26/21 at 3:37 pm to RedStickBR

Thought of the day:

Having read a bunch of financial history lately, I’ve been trying to come up with a working definition of a “bubble.”

It’s tempting to point to valuation measures for this, but this is incomplete in that no one can say with any certainty how high is too high. It could in fact be the case that even a historically high price is not “too high.” For instance, if the last 5 Picasso paintings sold for between $1m and $5m, who’s to say the Picasso market has entered into a bubble if the next 2 sell for $10m? For all we know, someone could actually believe they are worth that much, and who are we to argue with that?

Thus, while quantitative metrics may be convincing circumstantial evidence for the presence of a bubble, they are not dispositive. Ultimately, bubbles are a behavioral phenomenon, which brings me to my working definition:

“A bubble is a period of time in financial markets in which the perceived risk/reward approaches the point of being impossible to play out in reality. This can be caused by an expectation of future return that is overwhelmingly too high to play out in reality or an expectation of future risk that is overwhelmingly too low to play out in reality or, as is most often the case, both. Said bubble typically resolves itself upon the final realization that said risk/reward relationship has entered the realm of impossibility.”

What do y’all think? Agree with this Quantitative + Behavioral approach to defining a bubble?

Having read a bunch of financial history lately, I’ve been trying to come up with a working definition of a “bubble.”

It’s tempting to point to valuation measures for this, but this is incomplete in that no one can say with any certainty how high is too high. It could in fact be the case that even a historically high price is not “too high.” For instance, if the last 5 Picasso paintings sold for between $1m and $5m, who’s to say the Picasso market has entered into a bubble if the next 2 sell for $10m? For all we know, someone could actually believe they are worth that much, and who are we to argue with that?

Thus, while quantitative metrics may be convincing circumstantial evidence for the presence of a bubble, they are not dispositive. Ultimately, bubbles are a behavioral phenomenon, which brings me to my working definition:

“A bubble is a period of time in financial markets in which the perceived risk/reward approaches the point of being impossible to play out in reality. This can be caused by an expectation of future return that is overwhelmingly too high to play out in reality or an expectation of future risk that is overwhelmingly too low to play out in reality or, as is most often the case, both. Said bubble typically resolves itself upon the final realization that said risk/reward relationship has entered the realm of impossibility.”

What do y’all think? Agree with this Quantitative + Behavioral approach to defining a bubble?

This post was edited on 1/26/21 at 3:38 pm

Posted on 1/26/21 at 4:35 pm to RedStickBR

Is it possible to identify bubbles in real time or only in hindsight?

Posted on 1/26/21 at 5:46 pm to Douglas Quaid

Possible to identify them? No.

Possible to identify signs of them? Yes.

They are similar to fires. You can’t conclude they’ve actually occurred until after they’ve ignited, but you can ascertain the signs before hand.

Possible to identify signs of them? Yes.

They are similar to fires. You can’t conclude they’ve actually occurred until after they’ve ignited, but you can ascertain the signs before hand.

Posted on 2/16/21 at 10:47 pm to RedStickBR

Nice little presentation from an economics professor at Northern Arizona University. It’s refreshing to see these lesser known economists simply speak their minds, without regard for what’s considered to be “mainstream” by the more prominent economists. It’s from 2019, but does good job breaking down the monetary base and explaining, in this professor’s view, why growth has been so stagnant.

LINK

LINK

Posted on 2/18/21 at 8:45 pm to RedStickBR

Posted on 2/19/21 at 9:53 am to RedStickBR

I'm currently reading "Why Nations Fail" recommended by Bennie

Posted on 2/19/21 at 10:20 am to wutangfinancial

Nice. Let me know how it is.

Posted on 2/19/21 at 1:19 pm to RedStickBR

It's interesting. It's a history of elitism essentially which is so fitting to the macro world right now. He uses some woke language but I'd expect that from an academic.

Posted on 2/19/21 at 3:24 pm to wutangfinancial

Posted on 3/16/21 at 11:06 am to RedStickBR

Posted on 4/5/21 at 11:26 am to RedStickBR

Popular

Back to top

1

1