- My Forums

- Tiger Rant

- LSU Recruiting

- SEC Rant

- Saints Talk

- Pelicans Talk

- More Sports Board

- Coaching Changes

- Fantasy Sports

- Golf Board

- Soccer Board

- O-T Lounge

- Tech Board

- Home/Garden Board

- Outdoor Board

- Health/Fitness Board

- Movie/TV Board

- Book Board

- Music Board

- Political Talk

- Money Talk

- Fark Board

- Gaming Board

- Travel Board

- Food/Drink Board

- Ticket Exchange

- TD Help Board

Customize My Forums- View All Forums

- Show Left Links

- Topic Sort Options

- Trending Topics

- Recent Topics

- Active Topics

Started By

Message

re: Endless Sleep - The Obituary Thread

Posted on 7/27/25 at 5:04 pm to Kafka

Posted on 7/27/25 at 5:04 pm to Kafka

LINK

quote:

Tom Lehrer, the sardonic singer-songwriter-pianist who rose to national fame after his dark, tartly funny topical songs were used on the comedic ‘60s TV news show “That Was the Week That Was,” has died at age 97.

Friends said that he was found dead in his home in Cambridge, Mass., on Saturday.

Lehrer, who acquired an underground audience in the early ‘50s with a pair of self-released albums, was by trade a professor who taught mathematics, first at Harvard and later in his career at UC Santa Cruz. He told one concert audience, “I don’t like people to get the idea that I have to do this for a living. I mean, it isn’t as though I had to do this. I could be making, oh, $3,000 a year just teaching.”

quote:"Tom Lehrer is the greatest satirical songwriter who ever lived" - Dr. Demento

A pioneer of musical black comedy during the optimistic Eisenhower years in America, Lehrer influenced the work that came later from such musical satirists as Randy Newman, “Weird Al” Yankovic and Harry Shearer.

The lean, bespectacled Lehrer essayed such then-taboo subjects as sexuality (“The Masochism Tango”), drug addiction (“The Old Dope Peddler”), homosexuality in the Boy Scouts (“Be Prepared”) and militarism (“It Makes a Fellow Proud to Be a Soldier”) on his early, self-released albums. Lehrer was lofted to fame by the caustic material he wrote for “TW3,” NBC’s U.S. spinoff of a popular British show hosted by the young David Frost.

His 1965 Reprise album “That Was the Year That Was” climbed to No. 18 on the American charts. Its razor-edged songs skewered prejudice (“National Brotherhood Week”), nuclear proliferation (“So Long Mom”) the Catholic Church (“The Vatican Rag”) and, appropriately, education (“The New Math”).

Posted on 7/27/25 at 10:21 pm to Kafka

I used to play "Vatican Rag"and "So Long, Mom" at my college radio station.

RIP, Tom

RIP, Tom

Posted on 7/27/25 at 10:28 pm to Kafka

Posted on 8/1/25 at 12:22 am to Kafka

LINK

quote:

Grammy Award-winning musical artist Flaco Jimenez has died, his family announced on his social media late Thursday night. He was 86.

quote:

The 86-year-old was known for his many achievements in Tejano music. One of his albums, “Partners,” was selected for the U.S. Library of Congress’s National Recording Registry in 2021.

The Library of Congress called Jimenez “a champion of traditional conjunto music and Tex-Mex culture who also is known for innovation and collaboration with a variety of artists.”

Posted on 8/1/25 at 1:57 pm to Kafka

Sandy Pinkard, Country Music’s Weird Al, Has Passed Away

quote:

Born James Sanford Pinkard Jr. on January 16, 1947, in Abbeville, Louisiana, Sandy joined the Air Force when he was younger, and served in the Vietnam War. When he returned to the states, Pinkard wanted to pursue being a country singer, but didn’t have much luck convincing a label to take a chance on him. That is when he turned to songwriting. As a songwriter without his tongue firmly implanted in his cheek, he co-wrote songs like the #1 hit for Mel Tillis, “Coca Cola Cowboy,” David Frizzell & Shelly West’s #1 duet “You’re The Reason God Made Oklahoma” that went on to win the 1981 ACM Song of the Year, the #1 song “Blessed Are the Believers” for Anne Murray in 1981, and Vern Gosdin’s #1 “I Can Tell By The Way You Dance.”

With his singing and writing partner Richard Bowden, they formed the comedy duo Pinkard & Bowden in 1984. Though the duo had original comedy songs as well like “I Lobster But Never Flounder,” parody songs is what became the duo’s signature. Signed to Warner Bros. Records, they released five albums between 1985 and 1993, and released 12 singles, including five that made the charts. Just looking through the titles of some of their parody songs is enough for a laugh.

“Mama She’s Lazy” (“Mama He’s Crazy” – The Judds)

“She Thinks I Steal Cars” (“She Thinks I Still Care” – George Jones)

“Drivin’ My Wife Away” (“Drivin’ My Life Away – Eddie Rabbitt)

“Blue Hairs Driving in My Lane” (“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” Willie Nelson)

“Delta Dawg” (“Delta Dawn” – Tanya Tucker)

“Help Me Make It Through the Yard” (“Help Me Make It Through The Night” – Sammi Smith)

“Libyan on a Jet Plane” (“Leaving on a Jet Plane” – John Denver)

“Somebody Done Somebody’s Song Wrong” (Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song – B.J. Thomas)

“Friends in Crawl Spaces” (“Friends in Low Places” – Garth Brooks)

Posted on 8/1/25 at 10:13 pm to PJinAtl

I absolutely loved Pinkard/Bowden.

In my song humor wheelhouse.

I loved Homer/Jethro too.

RIP

In my song humor wheelhouse.

I loved Homer/Jethro too.

RIP

Posted on 8/1/25 at 10:15 pm to PJinAtl

I used to play I Lobster(But Never Flounder) on my college radio station

Posted on 8/2/25 at 9:31 am to FightinTigersDammit

Jeannie Seely RIP

Country music trailblazer and Grand Ole Opry star Jeannie Seely died on Friday (Aug. 1) at Summit Medical Center in Hermitage, Tenn., due to complications from an intestinal infection. She was 85.

Country music trailblazer and Grand Ole Opry star Jeannie Seely died on Friday (Aug. 1) at Summit Medical Center in Hermitage, Tenn., due to complications from an intestinal infection. She was 85.

Posted on 8/5/25 at 11:40 pm to Kafka

LINK

quote:

Terry Reid, the artists’ artist who was revered by the likes of Aretha Franklin and Mick Jagger, and nearly became the lead singer of Led Zeppelin, has died, The Guardian reports. He was 75

quote:

With a reedy voice that could push to mighty and soulful heights, Reid earned the nickname “Superlungs” (partly a nod, too, to his rendition of the Donovan song, “Superlungs My Supergirl”). Between 1968 and 1978, Reid released five albums. And though he never scored a genuine chart hit, he garnered high praise from critics and esteem from his peers.

During the late Sixties, Reid opened for the Rolling Stones and Cream, and in 1968 Franklin famously stated: “There are only three things happening in England: the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, and Terry Reid.”

Posted on 8/7/25 at 7:31 pm to Kafka

Eddie Palmieri, Latin Music’s Dynamic Innovator, Dies at 88

He roped salsa into conversation with jazz, rock, funk and even modern classical music. “A new world music,” one critic said, “is being born.”

By Giovanni Russonello

Published Aug. 6, 2025

Updated Aug. 7, 2025, 11:42 a.m. ET

Eddie Palmieri, a pianist, composer and bandleader whose contributions to Afro-Caribbean music helped usher in the golden age of salsa in New York City, and whose far-reaching career established him as one of the great musical masterminds of the 20th century — not to mention one of its fieriest performers — died on Wednesday at his home in Hackensack, N.J. He was 88.

His youngest daughter, Gabriela Palmieri, confirmed the death, which she said came after “an extended illness.”

From the moment he founded his first steady band, the eight-piece La Perfecta, in 1961, Mr. Palmieri drove many of the stylistic shifts and creative leaps in Latin music. That group brought new levels of economy and jazz influence to a mambo scene that was just beginning to lose steam after its postwar boom, and it set the standard for what would become known as salsa. From there, he never stopped innovating.

In the 1970s, Mr. Palmieri roped salsa into conversation with jazz, rock, funk and even modern classical music on a series of highly regarded albums, including “Vamonos Pa’l Monte” and “The Sun of Latin Music,” as well as with the fusion band Harlem River Drive. He also teamed up with thoroughbred jazz musicians — Cal Tjader, Brian Lynch and Donald Harrison among them — making essential contributions to the subgenre of Latin jazz.

Mr. Palmieri’s fundamental tools, he once said in an interview, were the “complex African rhythmic patterns that are centuries old” and that lie at the root of Afro-Cuban music. “The intriguing thing for me is to layer jazz phrasings and harmony on top of those patterns,” he said. Explaining where he got his knack for dense and dissonant harmonies and his gleefully contrarian sense of rhythm, he cited jazz pianists like McCoy Tyner and Thelonious Monk as inspirations.

But the art historian and critic Robert Farris Thompson, writing in 1975 about the emergence of salsa, noticed other influences as well. “He blends avant-garde rock, Debussy, John Cage and Chopin without overwhelming the basic Afro-Cuban flavor,” he wrote of Mr. Palmieri. “A new world music, it might be said, is being born.”

For his part, Mr. Palmieri was never fond of the word “salsa.” He described his music in terms of its roots: “Afro-Cuban,” he said in a 2012 interview with the Smithsonian Oral History Project. Through the participation of Puerto Ricans and Nuyoricans like himself, he explained, it had become “Afro-Caribbean. And now it’s Afro-world.”

By the end of his life Mr. Palmieri was a highly decorated statesman in both jazz and Afro-Latin music. In 2013 he was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts and received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Latin Grammys.

Though he never graduated from high school, Mr. Palmieri was an endlessly curious and intensely intellectual man. He treated leading a band as both an art and a science, particularly after learning the Schillinger System of musical composition in the late 1960s. “What I learned intuitively — why it works, or why it excites you — now I learned it scientifically, from what I was able to capture from the Schillinger System,” he told the Smithsonian. “That has to do with rotary energy. That has to do with tension and resistance.”

One of his catchphrases was “I don’t guess I’m going to excite you with my band. I know it.”

Mr. Palmieri considered himself an ambassador of New York’s working-class and Puerto Rican neighborhoods, where he’d grown up playing stickball and dishing out egg creams at his father’s ice cream parlor. An ambassador, sure — but he could hardly be accused of acting like a diplomat: He lived by his own code, tangling often with music executives or institutions he found to be unfair or dealing in unsavory methods. At times that meant confronting one of the most mobbed-up executives in American music over unpaid royalties.

“You’re getting attacked constantly, one way or the other: fights with the promoters, fighting with the record labels,” Mr. Palmieri said. “So I went through all of this.”

For years he refused to pay taxes to the Internal Revenue Service, embracing the view of Henry George, an iconoclastic political economist whose ideas Mr. Palmieri had studied, that income tax was a legalized form of robbery.

Mr. Palmieri later used his eminent reputation to agitate successfully for greater inclusion of Latin music at the Grammys. The winner of eight trophies himself, he served for years as a member of the Recording Academy’s New York board of governors, helping to shepherd the creation of the Latin jazz album category in 1995.

When that category was eliminated in 2011, he wrote a letter accusing the academy of “marginalizing our music, culture and people even further.” The category was reinstated the next year.

But it wasn’t just a reputation for resistance that led Mr. Palmieri to be known as “the Madman of Salsa.” He looked the part onstage, sometimes jagging the piano keys with elbows and forearms, lunging and crying out, broadcasting catharsis.

In cooler moments he played without moving his head or shoulders at all, holding his body threateningly still, as if stalking his prey from deep grass. He would lightly growl as he held a stubborn ostinato or chased an arpeggio into the air. Before long he would be throwing himself at the instrument again, while remaining keenly aware of the ensemble.

LINK

He roped salsa into conversation with jazz, rock, funk and even modern classical music. “A new world music,” one critic said, “is being born.”

By Giovanni Russonello

Published Aug. 6, 2025

Updated Aug. 7, 2025, 11:42 a.m. ET

Eddie Palmieri, a pianist, composer and bandleader whose contributions to Afro-Caribbean music helped usher in the golden age of salsa in New York City, and whose far-reaching career established him as one of the great musical masterminds of the 20th century — not to mention one of its fieriest performers — died on Wednesday at his home in Hackensack, N.J. He was 88.

His youngest daughter, Gabriela Palmieri, confirmed the death, which she said came after “an extended illness.”

From the moment he founded his first steady band, the eight-piece La Perfecta, in 1961, Mr. Palmieri drove many of the stylistic shifts and creative leaps in Latin music. That group brought new levels of economy and jazz influence to a mambo scene that was just beginning to lose steam after its postwar boom, and it set the standard for what would become known as salsa. From there, he never stopped innovating.

In the 1970s, Mr. Palmieri roped salsa into conversation with jazz, rock, funk and even modern classical music on a series of highly regarded albums, including “Vamonos Pa’l Monte” and “The Sun of Latin Music,” as well as with the fusion band Harlem River Drive. He also teamed up with thoroughbred jazz musicians — Cal Tjader, Brian Lynch and Donald Harrison among them — making essential contributions to the subgenre of Latin jazz.

Mr. Palmieri’s fundamental tools, he once said in an interview, were the “complex African rhythmic patterns that are centuries old” and that lie at the root of Afro-Cuban music. “The intriguing thing for me is to layer jazz phrasings and harmony on top of those patterns,” he said. Explaining where he got his knack for dense and dissonant harmonies and his gleefully contrarian sense of rhythm, he cited jazz pianists like McCoy Tyner and Thelonious Monk as inspirations.

But the art historian and critic Robert Farris Thompson, writing in 1975 about the emergence of salsa, noticed other influences as well. “He blends avant-garde rock, Debussy, John Cage and Chopin without overwhelming the basic Afro-Cuban flavor,” he wrote of Mr. Palmieri. “A new world music, it might be said, is being born.”

For his part, Mr. Palmieri was never fond of the word “salsa.” He described his music in terms of its roots: “Afro-Cuban,” he said in a 2012 interview with the Smithsonian Oral History Project. Through the participation of Puerto Ricans and Nuyoricans like himself, he explained, it had become “Afro-Caribbean. And now it’s Afro-world.”

By the end of his life Mr. Palmieri was a highly decorated statesman in both jazz and Afro-Latin music. In 2013 he was named a Jazz Master by the National Endowment for the Arts and received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Latin Grammys.

Though he never graduated from high school, Mr. Palmieri was an endlessly curious and intensely intellectual man. He treated leading a band as both an art and a science, particularly after learning the Schillinger System of musical composition in the late 1960s. “What I learned intuitively — why it works, or why it excites you — now I learned it scientifically, from what I was able to capture from the Schillinger System,” he told the Smithsonian. “That has to do with rotary energy. That has to do with tension and resistance.”

One of his catchphrases was “I don’t guess I’m going to excite you with my band. I know it.”

Mr. Palmieri considered himself an ambassador of New York’s working-class and Puerto Rican neighborhoods, where he’d grown up playing stickball and dishing out egg creams at his father’s ice cream parlor. An ambassador, sure — but he could hardly be accused of acting like a diplomat: He lived by his own code, tangling often with music executives or institutions he found to be unfair or dealing in unsavory methods. At times that meant confronting one of the most mobbed-up executives in American music over unpaid royalties.

“You’re getting attacked constantly, one way or the other: fights with the promoters, fighting with the record labels,” Mr. Palmieri said. “So I went through all of this.”

For years he refused to pay taxes to the Internal Revenue Service, embracing the view of Henry George, an iconoclastic political economist whose ideas Mr. Palmieri had studied, that income tax was a legalized form of robbery.

Mr. Palmieri later used his eminent reputation to agitate successfully for greater inclusion of Latin music at the Grammys. The winner of eight trophies himself, he served for years as a member of the Recording Academy’s New York board of governors, helping to shepherd the creation of the Latin jazz album category in 1995.

When that category was eliminated in 2011, he wrote a letter accusing the academy of “marginalizing our music, culture and people even further.” The category was reinstated the next year.

But it wasn’t just a reputation for resistance that led Mr. Palmieri to be known as “the Madman of Salsa.” He looked the part onstage, sometimes jagging the piano keys with elbows and forearms, lunging and crying out, broadcasting catharsis.

In cooler moments he played without moving his head or shoulders at all, holding his body threateningly still, as if stalking his prey from deep grass. He would lightly growl as he held a stubborn ostinato or chased an arpeggio into the air. Before long he would be throwing himself at the instrument again, while remaining keenly aware of the ensemble.

LINK

Posted on 8/11/25 at 2:46 pm to Mizz-SEC

Bobby Whitlock, Derek and the Dominos Co-Founder and Session Player for George Harrison and Others, Dies at 77

LINK

Aug 10, 2025

By Chris Willman

Bobby Whitlock, the keyboard player and vocalist who co-founded Derek and the Dominos with Eric Clapton and played on classic albums like George Harrison‘s “All Things Must Pass,” died Sunday at age 77.

His manager, Carol Kaye, confirmed to Variety that Whitlock died Sunday morning at 1:20 a.m. after a brief bout with cancer.

The Memphis-born musician was signed to Stax Records at an early age and played with artists like Booker T. and the MG’s and Sam & Dave on his way up before becoming an integral member of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, during which he forged an alliance on tour with Clapton.

Derek and the Dominos turned out to be a one-album wonder, but what a “one album” — the 1971 double LP “Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs” is considered by many to be one of rock’s greatest albums. Whitlock co-wrote seven of its tracks, including “Bell Bottom Blues,” “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” and “Tell the Truth.”

“That thing was like lightning in a bottle,” Whitlock told Best Classic Bands in 2015. “We did one club tour, we did one photo session, then we did a tour of a bit larger venues. Then we did one studio album in Miami. We did one American tour. Then we did one failed attempt at a second album.” He blamed the usual suspects for the click burnout — “Everybody was doing entirely too much drugs and alcohol,” and there were ego conflicts between other members of the band, he said — but Whitlock had some company in contending that, while they lasted, Derek and the Dominos were “the very best band on the planet… We were better than anybody.”

After the breakup of that supergroup, he went on to release a series of solo albums in the 1970s, starting with “Bobby Whitlock” in 1972, which included all the members of the recently split group, albeit not all on the same tracks.

He also made an uncredited appearance on the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” and made the claim that he was cheated out of a rightful co-writing credit for the song “I Just Want to See His Face,” which he said he came up with with Mick Jagger while Keith Richards was not around.

His other credits as a guest musician include self-titled albums by Clapton and Doris Troy, Dr. John’s “The Sun, Moon & Herbs” and Stephen Stills & Manassas’ “Down the Road.”

Whitlock grew up in a hard-scrabble as the son of a minister, but described his upbringing as abusive. He found escape as a teenager in Memphis in the mid-’60s playing in a group called the Counts. “I wasn’t into the Rolling Stones or Beatles or anything like that. I was into the soul music that was coming out of Memphis,” he told Stephen Peeples. He was signed to a new label that Stax was founding, Hip Records, but it was one that was meant to release British Invasion-type music, and the fit just didn’t work out — Whitlock left the label without releasing anything, complaining that Stax saw him more as a potential bubblegum artist. Nonetheless, he thrived on learning at the feet of musicians like Steve Cropper and Booker T. and being around as many of the greatest soul records of the ’60s were being created.

Then Duck Dunn brought Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett to see his band at a local club, and they invited him to join them in California. “I hadn’t been any further (west) than Texarkana in Texas, so I said, ‘Hell, yeah!’ right there in front of Duck and everybody. And so I was gone in two days after that. We started Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, just Delaney and Bonnie and myself.”

Clapton was in a period when he did not want to be known as a solo act but be involved in band situations. That manifested in his tour and live album with Delaney and Bonnie. When most of the members of that ensemble went on to work with Joe Cocker, Whitlock held on as the remaining “…and Friend” before he reunited with Clapton, for the Harrison album and Derek and the Dominos.

Interestingly, Whitlock hated the coda of the band’s most famous number, “Layla.” “The song was complete without the coda,” he said. “The original single didn’t have it on it, and the few times that we did it [live] we didn’t do it then either. Plus, there’s the added fact that it is stolen goods. Jim Gordon got the piano melody from a song that he and his then girlfriend Rita Coolidge wrote together called ‘Time.’ Jim took the melody to the song and added it as the piano part. So he ripped it off from his girlfriend and didn’t give her writer’s credit for it. In my opinion, the piano part taints the integrity of this beautiful heart-on-the-line, soul-exposed-for-the-world-to-see song that Eric Clapton wrote entirely by himself.”

Talking of that period with the Houston Press in 2011, Whitlock said, “We were getting along pretty good until the hard drugs came into play. Jim and Carl and me had been together for several years prior to the Dominos thing, and we always got along really well. Jim was a great guy when he was straight. But when he started getting heavily involved in heroin and coke an booze, his personality changed drastically. I am very happy that the one studio record was the ‘one’ and that was it. It never will have anything other than itself to be compared to. It was the beginning and the end, and the all and all of itself — it’s magnum and opus all wrapped up in one.”

LINK

Aug 10, 2025

By Chris Willman

Bobby Whitlock, the keyboard player and vocalist who co-founded Derek and the Dominos with Eric Clapton and played on classic albums like George Harrison‘s “All Things Must Pass,” died Sunday at age 77.

His manager, Carol Kaye, confirmed to Variety that Whitlock died Sunday morning at 1:20 a.m. after a brief bout with cancer.

The Memphis-born musician was signed to Stax Records at an early age and played with artists like Booker T. and the MG’s and Sam & Dave on his way up before becoming an integral member of Delaney & Bonnie and Friends, during which he forged an alliance on tour with Clapton.

Derek and the Dominos turned out to be a one-album wonder, but what a “one album” — the 1971 double LP “Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs” is considered by many to be one of rock’s greatest albums. Whitlock co-wrote seven of its tracks, including “Bell Bottom Blues,” “Why Does Love Got to Be So Sad?” and “Tell the Truth.”

“That thing was like lightning in a bottle,” Whitlock told Best Classic Bands in 2015. “We did one club tour, we did one photo session, then we did a tour of a bit larger venues. Then we did one studio album in Miami. We did one American tour. Then we did one failed attempt at a second album.” He blamed the usual suspects for the click burnout — “Everybody was doing entirely too much drugs and alcohol,” and there were ego conflicts between other members of the band, he said — but Whitlock had some company in contending that, while they lasted, Derek and the Dominos were “the very best band on the planet… We were better than anybody.”

After the breakup of that supergroup, he went on to release a series of solo albums in the 1970s, starting with “Bobby Whitlock” in 1972, which included all the members of the recently split group, albeit not all on the same tracks.

He also made an uncredited appearance on the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” and made the claim that he was cheated out of a rightful co-writing credit for the song “I Just Want to See His Face,” which he said he came up with with Mick Jagger while Keith Richards was not around.

His other credits as a guest musician include self-titled albums by Clapton and Doris Troy, Dr. John’s “The Sun, Moon & Herbs” and Stephen Stills & Manassas’ “Down the Road.”

Whitlock grew up in a hard-scrabble as the son of a minister, but described his upbringing as abusive. He found escape as a teenager in Memphis in the mid-’60s playing in a group called the Counts. “I wasn’t into the Rolling Stones or Beatles or anything like that. I was into the soul music that was coming out of Memphis,” he told Stephen Peeples. He was signed to a new label that Stax was founding, Hip Records, but it was one that was meant to release British Invasion-type music, and the fit just didn’t work out — Whitlock left the label without releasing anything, complaining that Stax saw him more as a potential bubblegum artist. Nonetheless, he thrived on learning at the feet of musicians like Steve Cropper and Booker T. and being around as many of the greatest soul records of the ’60s were being created.

Then Duck Dunn brought Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett to see his band at a local club, and they invited him to join them in California. “I hadn’t been any further (west) than Texarkana in Texas, so I said, ‘Hell, yeah!’ right there in front of Duck and everybody. And so I was gone in two days after that. We started Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, just Delaney and Bonnie and myself.”

Clapton was in a period when he did not want to be known as a solo act but be involved in band situations. That manifested in his tour and live album with Delaney and Bonnie. When most of the members of that ensemble went on to work with Joe Cocker, Whitlock held on as the remaining “…and Friend” before he reunited with Clapton, for the Harrison album and Derek and the Dominos.

Interestingly, Whitlock hated the coda of the band’s most famous number, “Layla.” “The song was complete without the coda,” he said. “The original single didn’t have it on it, and the few times that we did it [live] we didn’t do it then either. Plus, there’s the added fact that it is stolen goods. Jim Gordon got the piano melody from a song that he and his then girlfriend Rita Coolidge wrote together called ‘Time.’ Jim took the melody to the song and added it as the piano part. So he ripped it off from his girlfriend and didn’t give her writer’s credit for it. In my opinion, the piano part taints the integrity of this beautiful heart-on-the-line, soul-exposed-for-the-world-to-see song that Eric Clapton wrote entirely by himself.”

Talking of that period with the Houston Press in 2011, Whitlock said, “We were getting along pretty good until the hard drugs came into play. Jim and Carl and me had been together for several years prior to the Dominos thing, and we always got along really well. Jim was a great guy when he was straight. But when he started getting heavily involved in heroin and coke an booze, his personality changed drastically. I am very happy that the one studio record was the ‘one’ and that was it. It never will have anything other than itself to be compared to. It was the beginning and the end, and the all and all of itself — it’s magnum and opus all wrapped up in one.”

Posted on 8/11/25 at 2:47 pm to Mizz-SEC

After not having released a solo album since 1976, Whitlock — who had been semi-retired in Mississippi for many years — came back in 1999 with his fourth album, aptly titled “It’s About Time.” But, by his own account, he was “going crazy” at that time from taking too many meds prescribed for an inner ear condition and serious vertigo.

Then British TV host Jools Holland had invited him and Clapton to make a joint appearance on “Later… with Jools Holland,” even though the two former close collaborators had not seen in each other in nearly three decades.

“I was on all those meds and still drinking wine. My whole insides were convulsing,” he told Best Classic Bands. “I then saw Eric sitting there across the room… And there was a sense of peace about him, an aura of peace. And… I wanted that. I knew that (the real) Bobby, the guy that is talking to you here now, is not shrouded with all these pharmaceuticals and alcohol. I remembered me while in the throes of all that. And I said, I want my life back. And pretty much six months afterwards to the day after I had that epiphany, I called it all off.”

Whitlock had sold off his rights to Derek and the Dominos’ royalties many years prior, but he said Clapton and his manager helped get them back. There was also a settlement, Whitlock said, with Clapton over the authorship of “Bell Bottom Blues.” In the meantime, the musician credited his royalties from jam sessions that made up the third disc of the “All Things Must Pass” 3-LP set for his ability to make ends meet. “That’s been paying my electricity my whole life,” he said.

When it came to the highly contentious credits for “All Things Must Pass,” Whitlock was adamant that he was the dominant keyboard player on the classic album, saying that Harrison “asked me and Eric to put together the core band and to be the core band for the album… If I had only done hand-claps or sang a background part on this great album, that would have carried me for the rest of my life,” he said in a 2021 YouTube video, when the album was getting a remix and deluxe re-release. “But, fortunately, I played on pretty much and sang on everything. On ‘My Sweet Lord,’ that’s just George and me singing background… I was there when the doors [to the studio] opened and I was there when they closed. I did not miss one session. I even went to the two Pete Drake sessions because I wanted to say that I had been to every session… I can tell you right now, Gary Wright isn’t playing the B3 on ‘Let it Down.’ It’s me… All the Hammond organ, I’m playing. So anytime you hear a Hammond… Billy Preston is playing a grand piano. That’s how it really went.”

In the early 2000s, he began doing club shows with his wife, CoCo Carmel Whitlock (who formerly was married to Delaney Bramlett), performing the “Layla” songs acoustically.

“The songs on that album are as new today as they were then,” he said in a 2006 interview with the Austin Chronicle. “They just never had anyone perform them that had anything to do with them.” The shows resulted in a live album by the duo, “Other Assorted Love Songs,” in 2003.

After a brief sojourn in Tennessee (“I was a little too soulful for Nashville,” he laughed), Whitlock moved to Austin in 2006. “It reminds me of Memphis in 1965, when it was about the music, and everybody was supportive of everybody. Now I can’t imagine living anyplace else.”

In 2021, Whitlock and his wife moved away from Austin. He had been based in the small town of Ozona, Texas, according to his Facebook page.

In 2010, he released an autobiography, with a foreword by Clapton.

Whitlock was inducted into Memphis’ Beale Street Walk of Fame in 2024.

Last year, speaking with the Everything Knoxville site in conjunction with his Memphis honor, Whitlock said, “There was a point in time where I really didn’t think anybody cared. I knew they acknowledged my input on all those great records, you know, ‘Layla’ and ‘All Things Must Pass’ — there’s a list of them. … My business is to try to conduct myself as a decent person and a gentleman as much as I can, get through this world, navigate through this without making too many waves. But when you make them, make them big – ones to remember… All of the sudden, everything seems to have turned around, and I wasn’t looking for it, that’s for sure.

“I knew my input and I was good with it. I was all right with myself whether anybody ever acknowledged anything I’ve ever done or not,” he continued. “I’ve got a great life. I paint every day. I’m really good with doing what I do. It’s just another extension of who I am. And I’ve been blessed in each and every way; everywhere I turn around, you know, it’s just nothing but a blessing for me.”

In recent years, he had undertaken painting and had hundreds of his pieces displayed in galleries in Texas.

Besides his wife, he is survived by three children, Ashley Brown, Beau Whitlock and Tim Whitlock Kelly, and his sister Debbie Wade.

Posted on 8/20/25 at 9:37 am to Mizz-SEC

Maybe some of you knew who Art Fein was, but for me he was a semi-recent discovery.

His 1980's and 90's cable access are being posted to YouTube and are all treasures. RIP Art.

-------------------------------------

Art Fein, Los Angeles rock-scene renaissance man, dead at 79

By August Brown

Staff Writer

Aug. 12, 2025 4:16 PM PT

Art Fein, a Los Angeles music-scene renaissance man who worked as a journalist, publicist, manager and television host over a six-decade career, has died. He was 79.

Fein died of heart failure on July 30 while recovering from surgery for a broken hip, according to Cliff Burnstein, co-founder of Q Prime Management and a longtime friend.

Arthur David Fein was born June 17, 1946. Growing up in Chicago, he was transfixed by a Chuck Berry concert at age 10 and devoted his life to discovering, championing and preserving rock music. After moving to Los Angeles in 1971 to pursue a career in music journalism, he got a job in Capitol Records’ then-nascent college promotion department. There, he befriended John Lennon and Yoko Ono, while coordinating interviews with college radio stations for Ono’s latest album, “Approximately Infinite Universe.”

After leaving Capitol, he wrote music reviews for the Los Angeles Times, Herald-Examiner, Billboard and others before being hired as music editor at Variety. “By the time I got this job, I was sick of the new, aggravating profession of rock criticism,” he recalled in his 2022 memoir “Rock’s in My Head.” “It was about writers, not the music. I wasn’t interested in being terribly critical. I was an advocate. I wanted to help the music along; rock critics wanted to help their sense of superiority.”

He returned to the label world with stints at Elektra/Asylum and Casablanca but pivoted to management, incubating a proto-punk scene that would yield influential L.A. acts like the Cramps, the Blasters and the Heaters. A compilation he assembled, 1983’s “(Art Fein Presents) The Best of L.A. Rockabilly,” became a bible for bands inspired by X and Social Distortion, which drew from vintage rockabilly but amped it up for the punk age.

His public access cable TV show, “Lil Art’s Poker Party,” featured interviews and performances with his favorite musicians and ran in SoCal for 24 years. Rhino Records co-founder Richard Foos recalled that “for years we had a weekly poker game either at his house or mine. I was there the night [music critic] Lester Bangs was playing. We started the first hand, started talking music, and never played another hand.”

In 1990, Fein published “The L.A. Musical History Tour: A Guide to the Rock and Roll Landmarks of Los Angeles,” a compendium of locations guiding readers to grave sites of stars such as Roy Orbison and Ritchie Valens, and sites where Sam Cooke, Janis Joplin, Marvin Gaye, Tim Hardin, Dennis Wilson and Darby Crash died.

Fein also developed a complicated relationship with producer Phil Spector, to whom Lennon had introduced Fein as the man who “knows all about music.” Fein became part of Spector’s inner circle, even into his deeply troubled years when he was convicted of murdering House of Blues hostess Lana Clarkson. Fein maintained contact with Spector even after he was sentenced to life in prison.

The Blasters’ lead guitarist Dave Alvin wrote on Facebook that “Back in the early days of The Blasters, when few outside of Rollin’ Rock Records knew or cared who we were, Art cared deeply. In early 1980, I was a wannabe poet working as a fry cook in Long Beach ... Art Fein played ‘Marie Marie’ to a Welsh rock ‘n’ roll singer named Shakin’ Stevens, who quickly recorded my song and made it into a huge international hit. ... Thanks to Art Fein, I was soon able to quit my job as a cook and pursue music. I can never, ever thank you enough for all you did for me, Art.”

Singer-songwriter-guitarist Rosie Flores added that “back in ‘94 when I was touring with Butch Hancock in Europe, I took a bad fall, at the end of our month-long tour. I slipped in the rain on a cobblestone street in London and severely broke my wrist. Three months later I was invited to sing at the Elvis [annual birthday] bash at The House of Blues ... It was normal protocol to donate all the money from the proceeds of the show and give it to an organization or a charity. This year, Art surprised me and handed me a stack of money to the tune of $1,500 for my medical bills. I didn’t expect that at all [and] it brought tears to my eyes.”

In the closing lines of his memoir, Fein wrote that “I can’t say anything terribly pithy or canny about the state of record sales, or streaming, or new delivery systems. Or how YouTube or TikTok are shaping contemporary music.”

“It turns out I didn’t want to be in the music business; I wanted to be in the music,” he wrote. “There I remain.”

Fein is survived by daughter Jessie and wife Jennifer.

LINK

His 1980's and 90's cable access are being posted to YouTube and are all treasures. RIP Art.

-------------------------------------

Art Fein, Los Angeles rock-scene renaissance man, dead at 79

By August Brown

Staff Writer

Aug. 12, 2025 4:16 PM PT

Art Fein, a Los Angeles music-scene renaissance man who worked as a journalist, publicist, manager and television host over a six-decade career, has died. He was 79.

Fein died of heart failure on July 30 while recovering from surgery for a broken hip, according to Cliff Burnstein, co-founder of Q Prime Management and a longtime friend.

Arthur David Fein was born June 17, 1946. Growing up in Chicago, he was transfixed by a Chuck Berry concert at age 10 and devoted his life to discovering, championing and preserving rock music. After moving to Los Angeles in 1971 to pursue a career in music journalism, he got a job in Capitol Records’ then-nascent college promotion department. There, he befriended John Lennon and Yoko Ono, while coordinating interviews with college radio stations for Ono’s latest album, “Approximately Infinite Universe.”

After leaving Capitol, he wrote music reviews for the Los Angeles Times, Herald-Examiner, Billboard and others before being hired as music editor at Variety. “By the time I got this job, I was sick of the new, aggravating profession of rock criticism,” he recalled in his 2022 memoir “Rock’s in My Head.” “It was about writers, not the music. I wasn’t interested in being terribly critical. I was an advocate. I wanted to help the music along; rock critics wanted to help their sense of superiority.”

He returned to the label world with stints at Elektra/Asylum and Casablanca but pivoted to management, incubating a proto-punk scene that would yield influential L.A. acts like the Cramps, the Blasters and the Heaters. A compilation he assembled, 1983’s “(Art Fein Presents) The Best of L.A. Rockabilly,” became a bible for bands inspired by X and Social Distortion, which drew from vintage rockabilly but amped it up for the punk age.

His public access cable TV show, “Lil Art’s Poker Party,” featured interviews and performances with his favorite musicians and ran in SoCal for 24 years. Rhino Records co-founder Richard Foos recalled that “for years we had a weekly poker game either at his house or mine. I was there the night [music critic] Lester Bangs was playing. We started the first hand, started talking music, and never played another hand.”

In 1990, Fein published “The L.A. Musical History Tour: A Guide to the Rock and Roll Landmarks of Los Angeles,” a compendium of locations guiding readers to grave sites of stars such as Roy Orbison and Ritchie Valens, and sites where Sam Cooke, Janis Joplin, Marvin Gaye, Tim Hardin, Dennis Wilson and Darby Crash died.

Fein also developed a complicated relationship with producer Phil Spector, to whom Lennon had introduced Fein as the man who “knows all about music.” Fein became part of Spector’s inner circle, even into his deeply troubled years when he was convicted of murdering House of Blues hostess Lana Clarkson. Fein maintained contact with Spector even after he was sentenced to life in prison.

The Blasters’ lead guitarist Dave Alvin wrote on Facebook that “Back in the early days of The Blasters, when few outside of Rollin’ Rock Records knew or cared who we were, Art cared deeply. In early 1980, I was a wannabe poet working as a fry cook in Long Beach ... Art Fein played ‘Marie Marie’ to a Welsh rock ‘n’ roll singer named Shakin’ Stevens, who quickly recorded my song and made it into a huge international hit. ... Thanks to Art Fein, I was soon able to quit my job as a cook and pursue music. I can never, ever thank you enough for all you did for me, Art.”

Singer-songwriter-guitarist Rosie Flores added that “back in ‘94 when I was touring with Butch Hancock in Europe, I took a bad fall, at the end of our month-long tour. I slipped in the rain on a cobblestone street in London and severely broke my wrist. Three months later I was invited to sing at the Elvis [annual birthday] bash at The House of Blues ... It was normal protocol to donate all the money from the proceeds of the show and give it to an organization or a charity. This year, Art surprised me and handed me a stack of money to the tune of $1,500 for my medical bills. I didn’t expect that at all [and] it brought tears to my eyes.”

In the closing lines of his memoir, Fein wrote that “I can’t say anything terribly pithy or canny about the state of record sales, or streaming, or new delivery systems. Or how YouTube or TikTok are shaping contemporary music.”

“It turns out I didn’t want to be in the music business; I wanted to be in the music,” he wrote. “There I remain.”

Fein is survived by daughter Jessie and wife Jennifer.

LINK

Posted on 8/27/25 at 9:25 pm to Mizz-SEC

This one fell through the cracks. RIP

Jeannie Seely, Who Pushed Boundaries at the Grand Ole Opry, Dies at 85

She blazed a trail for women in country music with the candor of her songs and her bold fashion sense. She was the first woman to host a segment on the Opry.

By Bill Friskics-Warren

Published Aug. 1, 2025

Jeannie Seely, who in the 1960s helped transform the image of women in country music from demure, gingham-clad helpmeet to self-possessed free spirit, died on Friday in Hermitage, Tenn., a suburb of Nashville. She was 85.

Her death, in a hospital, was announced by the Country Music Association. The cause was an intestinal infection, said Don Murry Grubbs, Ms. Seely’s publicist.

A mainstay of the Grand Ole Opry for more than five decades, Ms. Seely had more than a dozen Top 40 country hits between 1966 and 1974. She was known as “Miss Country Soul” for the torch-like quality of her vocals.

Her most popular recording, “Don’t Touch Me,” reached No. 2 on the Billboard country chart and crossed over to the mainstream Hot 100 in 1966. A sensual ballad whose lyrics stress emotional commitment over sexual gratification, the song has been covered by numerous artists, including the folk singer Carolyn Hester, the reggae artist Nicky Thomas and the soul music pioneer Etta James.

The song won Ms. Seely the Grammy Award for best female country vocal performance in 1967. The record’s less-is-more arrangement — slip-note piano, sympathetic background singers and sighing steel guitar — was vintage Nashville Sound on the cusp of “countrypolitan,” its pop-inflected successor.

“Don’t open the door to heaven if I can’t come in/Don’t touch me if you don’t love me,” Ms. Seely admonishes her lover, her voice abounding with unfulfilled desire.

“To have you, then lose you, wouldn’t be smart on my part,” she sings in the final stanza. She tortures the word “part” for two measures until her voice breaks and, with it, it seems, her heart.

Written by Hank Cochran, who would become Ms. Seely’s husband, “Don’t Touch Me” anticipated Sammi Smith’s breathtakingly intimate version of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” which was released four years later. “Don’t Touch Me,” the critic Robert Christgau wrote, “took country women’s sexuality from the honky-tonk into the bedroom.”

Ms. Seely blazed a trail for women in country music for the candor of her songs, and for wearing miniskirts and go-go boots on the Opry stage, bucking the gingham-and-calico dress code embraced by some of her more matronly predecessors like Kitty Wells and Dottie West. In the 1980s, she became the first woman to host her own segment on the typically conservative and patriarchal Opry.

“I was the main woman that kept kicking on that door to get to host the Opry segments,” Ms. Seely told the Nashville Scene newspaper in 2005. “I used to say to my former manager Hal Durham, ‘Tell me again why is it women can’t host on the Opry?’ He’d rock on his toes and jingle his change and say, ‘It’s tradition, Jeannie.’ And I’d say, ‘Oh, that’s right. It’s tradition. It just smells like discrimination.’”

Ms. Seely worked with top-tier Nashville session players who were attuned to the soulful sounds in Memphis and Muscle Shoals, Ala., to build a career around recordings that plumbed themes of infidelity, heartbreak and female emancipation.

The titles of some of her singles spoke volumes: “All Right (I’ll Sign the Papers)” (1971), about the ravages of divorce; “Welcome Home to Nothing” (1968), about a marriage gone cold; and “Take Me to Bed” (1978). Her unflinching vocals told the rest of the story.

“Can I Sleep in Your Arms,” an intimacy-starved rewrite of the Depression-era lament, “Can I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight, Mister,” was a Top 10 country hit in 1973. (Two years later, Willie Nelson recorded the song for his groundbreaking concept album, “Red Headed Stranger.”)

Marilyn Jeanne Seeley was born on July 6, 1940, in Titusville, Pa., and grew up in nearby Townville. (She later changed the spelling of her surname.) She was the youngest of four children of Leo and Irene Seeley. Her father, a farmer and steel mill worker, played banjo and called square dances on weekends. Her mother sang in the kitchen while baking bread on Saturdays.

Ms. Seely was 11 when she first performed on the radio station WMGW in Meadville, Pa. “I can still remember standing on a stack of wooden soda cases because I wasn’t tall enough to reach the unadjustable microphones,” she recalled on her website.

After graduating from high school, where she was a cheerleader and honor student, she took a job with the Titusville Trust Company. Three years later, she moved to California and went to work at a bank in Beverly Hills.

A job as a secretary at Imperial Records in Hollywood opened doors in the music business, and she found early success as a songwriter with “Anyone Who Knows What Love Is (Will Understand).”

Written with a young Randy Newman and two other collaborators, the song reached the Hot 100 in a version by the New Orleans soul singer Irma Thomas in 1964. More than a half-century later, after having been recorded by Boyz II Men and others, it was used in episodes of the science-fiction TV series “Black Mirror.”

In 1965, Ms. Seely signed a contract with Challenge Records, the West Coast label owned by the country singer Gene Autry. The association yielded regional hits but no national exposure.

At the urging of Mr. Cochran, whom she married in 1969 (the couple later divorced), Ms. Seely moved to Nashville, where she signed with Fred Foster’s Monument Records and had her breakthrough hit, “Don’t Touch Me.”

She made her Opry debut in the summer of 1966 and briefly starred as the female singer on “The Porter Wagoner Show,” a nationally syndicated TV program, while also performing regularly with Ernest Tubb.

“My idea of ‘feminist,’” she once said, “is to make sure that women have the same choices that men have always had, and that we are respected for our roles — whatever they are — as much as any man is respected for his.

Ms. Seely’s biggest country hit as a songwriter came with “Leavin’ and Sayin’ Goodbye,” a chart-topping single for the singer Faron Young in 1972. Merle Haggard and Ray Price also recorded her originals.

In 1977, after a decade of hits, including a handful of Top 20 country duets with the crooner Jack Greene, she sustained serious injuries in an automobile accident that almost ended her career. Apart from appearing on the Opry and having a small part in the 1980 movie “Honeysuckle Rose,” which starred Mr. Nelson, she all but retired from performing. (Her other movie appearance was in 2002 in “Changing Hearts,” starring Faye Dunaway.)

In the 2000s, Ms. Seely increasingly turned her attention to bluegrass, recording an award-winning duet with Ralph Stanley. She also emerged as an elder stateswoman of the Opry, which remained her chief passion into the 2020s.

Her second husband, Gene Ward, whom she married in 2010, preceded her in death. She did not have any immediate survivors.

In 2005, with the country singers Kathy Mattea and Pam Tillis, Ms. Seely starred in a Nashville production of Eve Ensler’s “The Vagina Monologues.” It was second nature to her, she told Nashville Scene, to appear in such a politically charged play.

“I think of myself as a feminist,” she explained. “My idea of ‘feminist’ is to make sure that women have the same choices that men have always had, and that we are respected for our roles — whatever they are — as much as any man is respected for his.”

Jeannie Seely, Who Pushed Boundaries at the Grand Ole Opry, Dies at 85

She blazed a trail for women in country music with the candor of her songs and her bold fashion sense. She was the first woman to host a segment on the Opry.

By Bill Friskics-Warren

Published Aug. 1, 2025

Jeannie Seely, who in the 1960s helped transform the image of women in country music from demure, gingham-clad helpmeet to self-possessed free spirit, died on Friday in Hermitage, Tenn., a suburb of Nashville. She was 85.

Her death, in a hospital, was announced by the Country Music Association. The cause was an intestinal infection, said Don Murry Grubbs, Ms. Seely’s publicist.

A mainstay of the Grand Ole Opry for more than five decades, Ms. Seely had more than a dozen Top 40 country hits between 1966 and 1974. She was known as “Miss Country Soul” for the torch-like quality of her vocals.

Her most popular recording, “Don’t Touch Me,” reached No. 2 on the Billboard country chart and crossed over to the mainstream Hot 100 in 1966. A sensual ballad whose lyrics stress emotional commitment over sexual gratification, the song has been covered by numerous artists, including the folk singer Carolyn Hester, the reggae artist Nicky Thomas and the soul music pioneer Etta James.

The song won Ms. Seely the Grammy Award for best female country vocal performance in 1967. The record’s less-is-more arrangement — slip-note piano, sympathetic background singers and sighing steel guitar — was vintage Nashville Sound on the cusp of “countrypolitan,” its pop-inflected successor.

“Don’t open the door to heaven if I can’t come in/Don’t touch me if you don’t love me,” Ms. Seely admonishes her lover, her voice abounding with unfulfilled desire.

“To have you, then lose you, wouldn’t be smart on my part,” she sings in the final stanza. She tortures the word “part” for two measures until her voice breaks and, with it, it seems, her heart.

Written by Hank Cochran, who would become Ms. Seely’s husband, “Don’t Touch Me” anticipated Sammi Smith’s breathtakingly intimate version of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night,” which was released four years later. “Don’t Touch Me,” the critic Robert Christgau wrote, “took country women’s sexuality from the honky-tonk into the bedroom.”

Ms. Seely blazed a trail for women in country music for the candor of her songs, and for wearing miniskirts and go-go boots on the Opry stage, bucking the gingham-and-calico dress code embraced by some of her more matronly predecessors like Kitty Wells and Dottie West. In the 1980s, she became the first woman to host her own segment on the typically conservative and patriarchal Opry.

“I was the main woman that kept kicking on that door to get to host the Opry segments,” Ms. Seely told the Nashville Scene newspaper in 2005. “I used to say to my former manager Hal Durham, ‘Tell me again why is it women can’t host on the Opry?’ He’d rock on his toes and jingle his change and say, ‘It’s tradition, Jeannie.’ And I’d say, ‘Oh, that’s right. It’s tradition. It just smells like discrimination.’”

Ms. Seely worked with top-tier Nashville session players who were attuned to the soulful sounds in Memphis and Muscle Shoals, Ala., to build a career around recordings that plumbed themes of infidelity, heartbreak and female emancipation.

The titles of some of her singles spoke volumes: “All Right (I’ll Sign the Papers)” (1971), about the ravages of divorce; “Welcome Home to Nothing” (1968), about a marriage gone cold; and “Take Me to Bed” (1978). Her unflinching vocals told the rest of the story.

“Can I Sleep in Your Arms,” an intimacy-starved rewrite of the Depression-era lament, “Can I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight, Mister,” was a Top 10 country hit in 1973. (Two years later, Willie Nelson recorded the song for his groundbreaking concept album, “Red Headed Stranger.”)

Marilyn Jeanne Seeley was born on July 6, 1940, in Titusville, Pa., and grew up in nearby Townville. (She later changed the spelling of her surname.) She was the youngest of four children of Leo and Irene Seeley. Her father, a farmer and steel mill worker, played banjo and called square dances on weekends. Her mother sang in the kitchen while baking bread on Saturdays.

Ms. Seely was 11 when she first performed on the radio station WMGW in Meadville, Pa. “I can still remember standing on a stack of wooden soda cases because I wasn’t tall enough to reach the unadjustable microphones,” she recalled on her website.

After graduating from high school, where she was a cheerleader and honor student, she took a job with the Titusville Trust Company. Three years later, she moved to California and went to work at a bank in Beverly Hills.

A job as a secretary at Imperial Records in Hollywood opened doors in the music business, and she found early success as a songwriter with “Anyone Who Knows What Love Is (Will Understand).”

Written with a young Randy Newman and two other collaborators, the song reached the Hot 100 in a version by the New Orleans soul singer Irma Thomas in 1964. More than a half-century later, after having been recorded by Boyz II Men and others, it was used in episodes of the science-fiction TV series “Black Mirror.”

In 1965, Ms. Seely signed a contract with Challenge Records, the West Coast label owned by the country singer Gene Autry. The association yielded regional hits but no national exposure.

At the urging of Mr. Cochran, whom she married in 1969 (the couple later divorced), Ms. Seely moved to Nashville, where she signed with Fred Foster’s Monument Records and had her breakthrough hit, “Don’t Touch Me.”

She made her Opry debut in the summer of 1966 and briefly starred as the female singer on “The Porter Wagoner Show,” a nationally syndicated TV program, while also performing regularly with Ernest Tubb.

“My idea of ‘feminist,’” she once said, “is to make sure that women have the same choices that men have always had, and that we are respected for our roles — whatever they are — as much as any man is respected for his.

Ms. Seely’s biggest country hit as a songwriter came with “Leavin’ and Sayin’ Goodbye,” a chart-topping single for the singer Faron Young in 1972. Merle Haggard and Ray Price also recorded her originals.

In 1977, after a decade of hits, including a handful of Top 20 country duets with the crooner Jack Greene, she sustained serious injuries in an automobile accident that almost ended her career. Apart from appearing on the Opry and having a small part in the 1980 movie “Honeysuckle Rose,” which starred Mr. Nelson, she all but retired from performing. (Her other movie appearance was in 2002 in “Changing Hearts,” starring Faye Dunaway.)

In the 2000s, Ms. Seely increasingly turned her attention to bluegrass, recording an award-winning duet with Ralph Stanley. She also emerged as an elder stateswoman of the Opry, which remained her chief passion into the 2020s.

Her second husband, Gene Ward, whom she married in 2010, preceded her in death. She did not have any immediate survivors.

In 2005, with the country singers Kathy Mattea and Pam Tillis, Ms. Seely starred in a Nashville production of Eve Ensler’s “The Vagina Monologues.” It was second nature to her, she told Nashville Scene, to appear in such a politically charged play.

“I think of myself as a feminist,” she explained. “My idea of ‘feminist’ is to make sure that women have the same choices that men have always had, and that we are respected for our roles — whatever they are — as much as any man is respected for his.”

Posted on 9/5/25 at 7:25 pm to Kafka

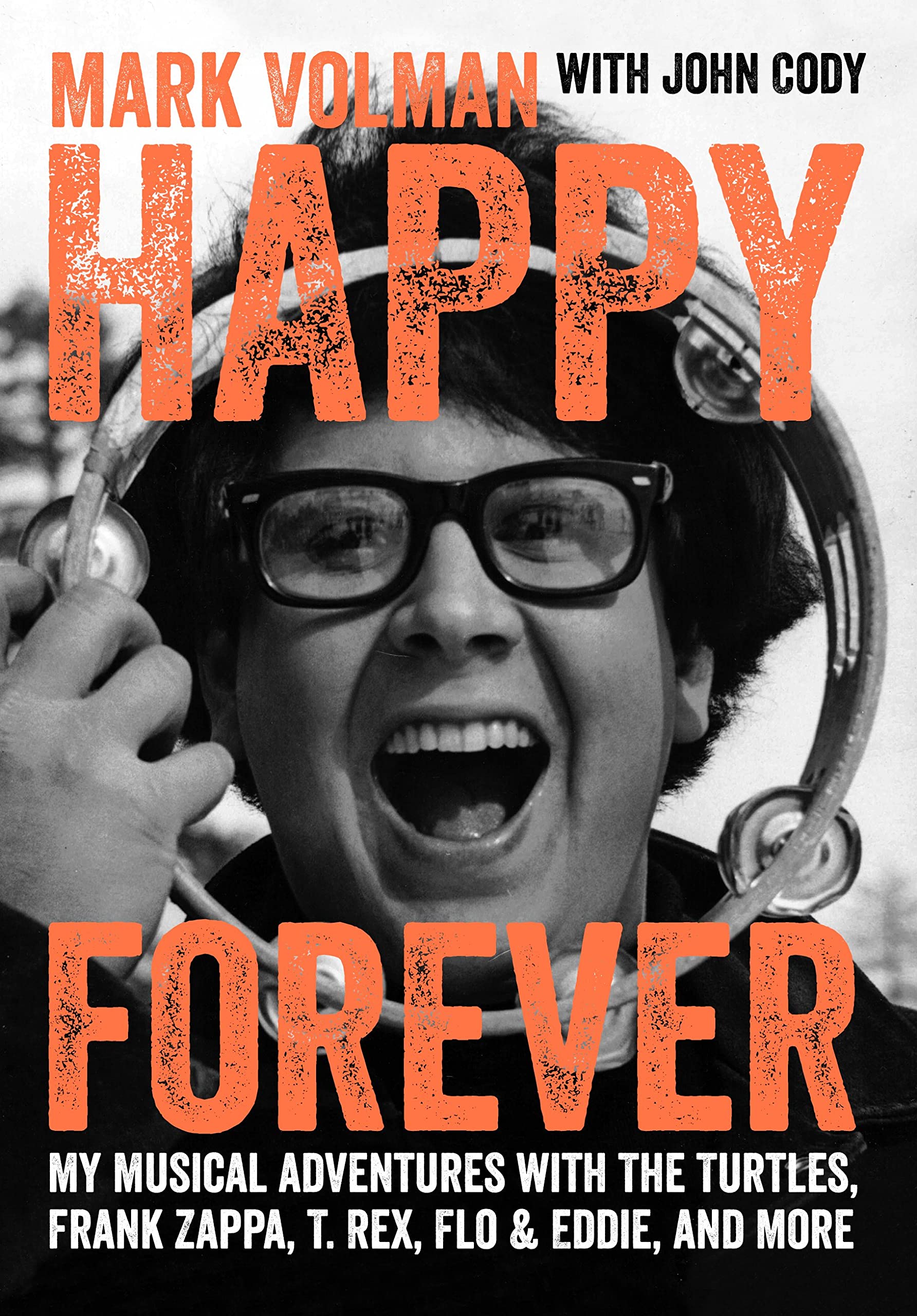

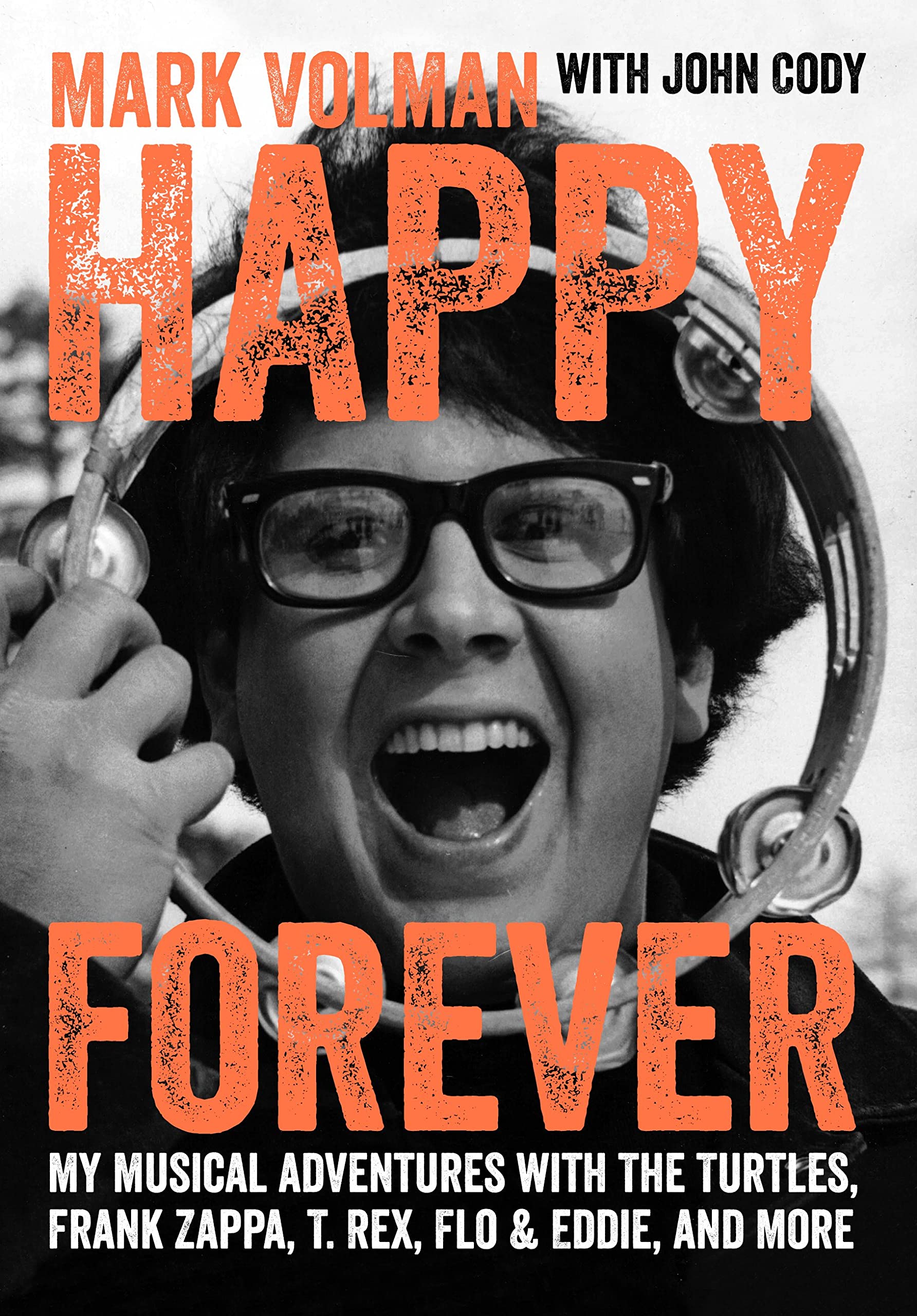

MARK VOLMAN, TURTLES, SINGER/SONGWRITER RIP

Mark Volman, a founding member of the 1960s pop group The Turtles sang on its No. 1 hit “Happy Together” and whose bright harmonies also fueled such songs “It Ain’t Me Babe,” “You Baby,” “She’d Rather Be with Me” and “Elenore,” died Friday in Nashville following a brief, unexpected illness. He was 78.

Volman revealed in 2023 that he had been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia in 2020, but he continued to perform on the annual “Happy Together” oldies tours in the years that followed.

Mark Volman, a founding member of the 1960s pop group The Turtles sang on its No. 1 hit “Happy Together” and whose bright harmonies also fueled such songs “It Ain’t Me Babe,” “You Baby,” “She’d Rather Be with Me” and “Elenore,” died Friday in Nashville following a brief, unexpected illness. He was 78.

Volman revealed in 2023 that he had been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia in 2020, but he continued to perform on the annual “Happy Together” oldies tours in the years that followed.

Posted on 9/5/25 at 8:56 pm to hogcard1964

Mark Volman obit

I was unaware until today that Volman wrote a memoir:

I've read Howard Kaylan's book - I was surprised by how little he mentioned Volman. Maybe they had a deal not to dish dirt on each other.

quote:

For much of his career, Volman worked closely with his friend Howard Kaylan, another co-founder of the Turtles and the band’s lead vocalist. After the Turtles disbanded, Volman and Kaylan linked up with Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, where they began to perform under the name Flo and Eddie. (Volman was “Flo,” which was short for “The Phlorescent Leech.”)

quote:A little known Turtles classic, written by Harry Nilsson

Along with their work with Zappa, Flo and Eddie released numerous albums of their own and scored a handful of films and TV shows. They also provided backing vocals for some of the biggest artists of the Seventies and Eighties, including John Lennon and Yoko Ono, T.Rex, Alice Cooper, Bruce Springsteen, Blondie, Stephen Stills, David Cassidy, Ray Manzarek, and Roger McGuinn.

I was unaware until today that Volman wrote a memoir:

I've read Howard Kaylan's book - I was surprised by how little he mentioned Volman. Maybe they had a deal not to dish dirt on each other.

Posted on 9/6/25 at 12:01 am to hogcard1964

Another sad day, indeed. I've come to really appreciate The Turtles, play their songs with my pals regularly and follow Howard Kaylan on Twitter. Bummer-bummer. RIP Mark.

Posted on 9/7/25 at 1:34 pm to Kafka

i met Volman briefly when my kid was touring Belmont

he was a prof in their music business department, he said every summer he organized a tour of other 60s era bands that was staffed entirely by his students, which sounded really cool (but not enough to justify the ridiculous tuition to go there)

he was a prof in their music business department, he said every summer he organized a tour of other 60s era bands that was staffed entirely by his students, which sounded really cool (but not enough to justify the ridiculous tuition to go there)

Posted on 9/7/25 at 2:34 pm to Kafka

Interesting

I thought they were best friends throughout life.

They (The Turtles) played at my old high school back in 1969. ...or maybe '70.

I thought they were best friends throughout life.

They (The Turtles) played at my old high school back in 1969. ...or maybe '70.

This post was edited on 9/7/25 at 2:37 pm

Posted on 9/7/25 at 3:00 pm to hogcard1964

quote:Maybe I'm just reading too much into it. But aside from telling how he got Volman into the band (the other members opposed adding a guy just to sing BG vocals -- yet their harmonies would be key to their breaking through), Kaylan doesn't really go into much detail about Volman. He's often around, but never really the focus of any stories after they hit it big. As I said, maybe they made a deal not to dish dirt on each other.

Interesting

I thought they were best friends throughout life

At one point, HK describes Marc Bolan as "my best friend".

Coming away from HK's book you don't really remember much about Volman. You recall more about Zappa, such as their visiting FZ on his deathbed, and him begging them for cigarettes.

Popular

Back to top

3

3